- Home

- Barbara Herman

Scent and Subversion Page 2

Scent and Subversion Read online

Page 2

Civet. Musk. Rotten fruit. Women’s underpants. Dirty ashtrays. Blood. This catalog of smells might seem out of place in a positive discussion of perfume, but all of these scents became metaphors for everything my modern, sterile office life lacked. In the virtual, deodorized, homogenized, and antiseptic world I felt myself dissolving into, these Things That Stink felt alive. As my journey through twentieth-century perfume continued, I began to see that even though perfume is thought of in the popular imagination as something to cover up our bad smells, in many ways, it can also be a meditation on the human body, if not an outright celebration of its riotous odors. A strange little book from the 1930s, Odoratus Sexualis, confirmed my suspicion. Its author Iwan Bloch claims that the animal notes in perfume were often used to highlight the body’s ripe and erotic odors rather than to cover them up.

The popularity of certain smells is cyclical, like hemlines and silhouettes in fashion. The nineteenth century’s popular “soliflore”—or single-note floral scent—was replaced by a new “abstract” perfume style. These abstract perfumes that didn’t attempt to mimic nature were made possible thanks to newly available synthetic perfume ingredients. Dirty, erotic animal notes that were popular in the mid-nineteenth century came back in the early part of the twentieth century and stuck around until even the 1980s, only to give way to the so-called “clean” fragrances of the 1990s. In the virtual Internet Age, perfume became disembodied, and the “baseness” of these base notes was repressed.

These cycles of taste mirror the arbitrary and ever shifting role of gender in perfume—the idea that certain scents are either masculine or feminine. If men wore violet perfumes in the nineteenth century and women wore tobacco and leather perfumes in the 1930s—styles whose “gender” has since been reversed—this seems like more proof in perfume form that gender, like perfume, is fluid, culturally constructed, and wearable in multiple forms on variable bodies.

Smell Bent: The Subculture of Perfume Lovers and the Resurgence of Scent

It’s a strange time for perfume. Laws are being created to ban fragrance in the workplace and in public spaces. The International Fragrance Association (IFRA), the regulatory body that is financed by scent makers such as Givaudan, IFF (International Flavors and Fragrances), and Symrise, is creating increasingly tighter restrictions and banning outright the use of important natural perfume ingredients for fear of their allergenic properties. But perfume is also experiencing a rebirth in the twenty-first century. Books like Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez’s Perfumes: The Guide and Chandler Burr’s The Perfect Scent have created a new audience of informed perfume lovers. A burgeoning group of niche perfumers is providing alternatives to mass-market scents. And the Internet is awash with perfume blogs written by amateur and expert perfume lovers from all over the world. With names like I Smell Therefore I Am, Perfume Posse, Now Smell This, and Australian Perfume Junkies, these blogs indicate an interest in the olfactory that seems to belie the idea that we live in scent-hostile times.

These perfume-centric online spaces—predominantly feminine and queer—represent a veritable subculture of women and men bonding over scent by discussing the aesthetics of perfume, and by reminiscing about scents they and their loved ones wore. People have always been interested in perfume, but an aesthetic and almost academic interest in perfume, a fascination with noncommercial brands, and the desire to talk about perfume seems to be something new altogether. In the past, you might have been encouraged to have a signature scent, or to buy the latest from Chanel, but you wouldn’t have been encouraged to know, as many perfume lovers do now, what aldehydes are, what the first perfume to have a synthetic ingredient in it was, or which “nose” created Chanel No. 5.

It’s a strange time for perfume

While the more conventional want to snatch up the ever-growing number of pseudo-celebrity scents (Paris Hilton’s Heiress, anyone, or Jersey Shore alum Snooki’s latest perfume?), a thriving group of olfactory rebels is seeking out vintage perfumes like Guerlain’s 1919 Mitsouko, or niche perfumes like CB I Hate Perfume’s Old Fur Coat, perfumes that challenge the idea of fragrance as mere ornament. These rebels exist alongside the perfume devotees intent on securing a place for classic twentieth-century perfumes in the pantheon, educating nascent perfume lovers, disseminating esoteric perfume history, and assuring perfume’s neglected cultural status as high art.

The Internet largely accounts for this burgeoning scent subculture by providing perfume education via blogs and forums; online marketplaces for full bottles and decants (milliliter-sized samples), so that perfume lovers can get a whiff of obscure and even vintage scents; perfume swaps on perfume forums between participants; and a community with whom they can discuss perfume. An introduction to the twentieth century’s greatest perfumes is often just a computer click away.

Smelling has become a serious hobby for some, and they’re championing our least-understood and oft-maligned sense. An interest in unconventional perfumes, in our virtual, computer-addicted, celeb-obsessed, and deodorized age, can be read as an act of cultural subversion. I have engaged in dialogue with these scent subversives over the past few years, and I proudly count myself among them.

Scent Is Subversive

Smell is an anarchist among our more socially reputable and mediated senses of vision, hearing, touch, and even taste. It is direct, instantaneous, and nonrational, and it provides data that can elicit in us the primal and the mysterious: sexual desire, appetite, emotion, fear, and memory. Smell bypasses the thalamus and penetrates into the oldest, most primitive part of the brain—the rhinencephalon, also known as the “nose brain” or the “olfactory brain.” The limbic system, the seat of our emotions and memories, resides in this “nose brain,” implicitly challenging the notion that there should be a hierarchy of senses, with smell at the bottom.

Since antiquity, our sense of smell has been both denigrated and exalted, viewed by philosophers with disdain yet also deemed sacred, incorporated for centuries into religious ceremonies and rituals connected to prayer and burial. Aristotle considered smell to be our least distinguished sense, dismissing it as fleeting, hard to analyze, and subordinate to emotion. For Plato, smells have no names and can only be defined relatively, in terms of other smells. Scent’s association with animal instinct and sexuality compounds its unsavory reputation.

Psychologist Wilhelm Fliess (1858–1928) believed that there was a close relationship between the nose and the genitals. Sigmund Freud saw a connection between sexual repression and evolved human beings’ diminished sense of smell, concluding that an atrophied olfactory ability was a precondition of civilization. Scent can be the invisible demarcation line that divides classes, ethnicities, and races. In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued that there are many prejudices we can get over, but smell repulsion is one of the most difficult.

“A bold fragrance? Perhaps, but why not let your perfume say the things you would not dare to?”

—PRIMITIF PERFUME AD BY MAX FACTOR (1956)

“There is something carnal about scent,” perfumer Christophe Laudamiel says. “When you look at a picture, you don’t feel the picture is inside you … Scent goes inside you because you have to breathe and because it’s made of molecules. So if I smell melon, there is a little bit of melon that comes inside of me so that I can detect it … If I look at La Joconde (Mona Lisa), I don’t feel like I’m swallowing La Joconde. So there is this extra feeling that makes scent maybe even more sexual, cannibalistic, or engaging.” The intensity and immediacy of smells can become, then, both the source of our fear and the source of their magic.

As a medium that addresses our often-maligned sense of smell, perfume is an inherently subversive art that has a rare opportunity to “speak” to us in its visceral language of aromatic notes. Yet sexism clearly contributes to perfume’s low status in our culture. In spite of the growing market for men’s scents, perfume is still considered a feminine art, a woman’s accessory, and, sadly, we still live in a culture in wh

ich that audience alone discredits it.

With their seminal books on perfume, Luca Turin, Tania Sanchez, and Chandler Burr have worked hard to turn around perfume’s status as cultural detritus and to give scent its due as an art just as complex, constructed, or deliberate as painting, music, or architecture. Calling perfumes “chemical poems” and emphasizing their aesthetics, Turin perhaps went in an extreme direction away from the usual discourse about perfume’s relation to memory, sex, and emotion in order to make a case for perfume as art. As if pleading with Aristotle and Plato on their terms, he claims in The Secret of Scent that perfume is not about memory or sex, but rather beauty and intelligence. And Chandler Burr has gone one step further in attempting to raise perfume’s cultural status by literally getting perfume its own museum wing. Thanks to his efforts, in the fall of 2012, NYC’s Museum of Art and Design devoted a portion of its space to an olfactory art exhibit that explored the aesthetics of 12 pivotal twentieth-century perfumes. But are memory, sex, and emotion separate from perfume’s aesthetics? Does perfume need this cultural elevation to be taken seriously?

The paradox and beauty of perfume is that it operates on multiple levels: the rational and the irrational; the visceral, the cognitive, and the aesthetic. Perfume’s power is that it has one foot in the elevated world of language, and one foot in the primal, emotional, and dreamlike. Perfumer Olivia Giacobetti celebrates perfume’s liminal status when she says that “Perfume is the language closest to the unconscious.”

We get cognitive pleasure from perfume. The pleasures of scent are not simply derived from emotions, sex, and gut reactions; they also comes from the satisfaction we get from decoding the meaning of fragrance. Perfume, as a synesthetic object, invites us to process it in a variety of languages, to indulge in synesthesia by translating perfume into shapes, colors, musical pitches, moods, visions, textures, personae, and even narratives. Yet for some, scent cannot enter the hallowed halls of Art. In The Art Instinct, Denis Dutton argues that smell cannot be art because it doesn’t inspire cognition; all it can do, he says, is to provoke nostalgia or memories. But smell scientist and author Avery Gilbert, and any other serious perfume lover, would beg to differ. “Contrary to conventional wisdom,” Gilbert argues on his blog FirstNerve.com, “especially among psychologists who should know better, olfaction is very cognitive. It requires attention, memory, comparison, naming and judgment. There is, after all, a thinking brain behind the smelling nose.”

It seems to me that efforts to elevate perfume to the level of art, worthy of recognition by arbiters of culture, ignore the fact that perfume doesn’t need their imprimatur. The way that scents are loved, disseminated, and analyzed on the wild, wild web nowadays suits its anarchic, nonhierarchical, and antiauthoritarian form. If the medium is the message, perfume’s message is subversive. It doesn’t need validation or ratification; its power is in the underground.

Perfume’s resurgence reflects a profound pendulum swing in our culture that marketers and branders might describe as a desire for authenticity. Perfume offers materiality in the Internet age of disembodied virtuality, an economy of touch, interactivity, and sensuality. In a pornified culture that has raised the visual to the apex of importance in sexuality, perfume shifts the focus of the erotic to the suggestive, the poetic, and the invisible.

There is no denying that perfume is a discourse aimed largely at women, providing a space in which they can express their erotic selves invisibly, autoerotically, and homosocially. Online perfume forums and blogs become occasions for women to talk to other women about their desires, appetites, and histories. It doesn’t take long for a discussion of perfume to wander into a memory of what one person wore in high school, or the scent of their mother or father or first lover.

Some perfumes are subversive because they threaten the American regime of clean and its corollary, scentphobia, by elevating dirty, animal, and bodily smells. “Americans,” Luca Turin has said, “are dedicated to the proposition that shit shouldn’t stink.” He’s not exaggerating by much. If you’re like most people in the United States, you’ve been encouraged to neglect your sense of smell. Like children who have retained a childish fear of foreignness, who associate smell with things dirty and unclean, and who think that everyone else’s home smells like cooked cabbage, you might have been taught to avoid smells. Perhaps you fear the smell of strange neighborhoods or cities, unfamiliar cooking smells, body odor (sadly, even your own!), and maybe, unless it’s antibacterial soap or shampoo, you fear anything that smells. A foray into the wild, wondrous world of perfume can help change that, as it did for me.

In our celebrity-obsessed, perfection-seeking, conventionally aspirational society, perfume invites us to embrace alternative values: the louche, the queer, and the decadent. Subversive perfumes in an already subversive medium posit an indie aesthetic that values art over commerce, niche over blockbuster, and individualism over conformity.

Smell is our underground sense and links us to sex, emotion, memory, and those messy things our allegedly logical culture tries to repress. In other words, scent is subversive, and Scent and Subversion is both a record and a reflection of my journey through twentieth-century perfume.

I view perfume as an aesthetic object of pop culture that is worthy of analysis, shaped by and shaping the culture in which it is embedded. Perfume is a language whose speech is worth learning and unpacking as one would a poem, book, or film. Scent is a path to getting closer to our senses, to instinct, and to our bodies and the earth at a time when those attachments are threatened. As I write this, Google Glasses are promising—or threatening, depending on your position on the ever-increasing encroachment of technology into our lives—to “bring information closer to your senses” by mediating our experience in the most extreme way to date, filling our sight lines with virtual information. As if we need to be even more divorced from our senses!

In Part I of Scent and Subversion, I discuss the path that led me to perfume and the exciting rise in scent-centric culture, including the online communities that continue to facilitate it.

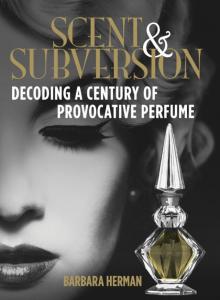

Part II includes descriptions and histories of more than three hundred vintage perfumes, decade by decade, from Jicky to Demeter’s Laundromat (2000), covering drugstore as well as haute perfumes. (A perfume can be considered vintage if it’s been discontinued, if its style is no longer “in,” or if it’s at least twenty years old.) Over the years, I’ve collected more than a hundred vintage perfume ads. Some of my favorites are sprinkled throughout the text, like movie posters to perfume’s invisible cinema.

Part III looks to the future through conversations with perfumers and scent provocateurs who are thinking about perfume in a profound way, some who are even rethinking its importance and purpose in society. Part III’s “A Brief History of Animal Notes in Perfume” explains the aesthetic, historical, and cultural importance of animal-derived ingredients that are no longer used in nonsynthetic form in perfumes, even as it acknowledges both the theoretical and real problems with sourcing animal notes from actual animals.

Finally, a Perfume Glossary helps elucidate terms used in this book, and will arm you with a vocabulary to begin your journey through scent.

I hope that Scent and Subversion inspires you to explore both vintage and contemporary perfume, to pay attention to the smells that surround us, and to see perfume as instructive, a bridge between the world and our oft-neglected sense of smell. Like reading poetry to understand the lyricism possible in demotic, everyday speech, smelling perfume connects us to the olfactory wonderland that is around us.

This 1938 perfume gets the ’60s treatment.

PART II

Twentieth-Century Perfume Profiles

The perfume that started its own category, François Coty’s 1917 Perfume Chypre (Cyprus in French) was named as an homage to the scents that perfumed that Greek island, which included citrus, floral, and moss notes.

The Icons of Modernity

Fougère Royale, Jicky, Chypre (1882–1919)

>

As single-note floral perfumes began to wane in popularity, perfumes with complex floral bouquets such as Houbigant’s Quelques Fleurs (1912) rose to prominence. With its overdose of raunchy civet, Guerlain’s Jicky (1889) retained the nineteenth century’s love of animalic notes, while bringing in a sense of abstraction to perfumery through a novel use of new synthetic ingredients. It combined notes and accords that, in their sum, smelled like nothing in the world. Even Fougère Royale (Royal Fern), with its beguiling name, didn’t smell like ferns but rather like bergamot, lavender, and coumarin, which at the time was a new and synthetic molecule found in abundance in tonka beans. Fougère, with that trio of notes, remains a perfume category today.

Unless otherwise specified, the perfume notes listed below each entry have come from various editions of Haarmann & Reimer’s The Fragrance Guide: Feminine and Masculine Notes—Fragrances on the International Market. In some cases, H&R’s notes are supplemented with additional sources.

Fougère Royale by Houbigant (1882)

Perfumer: Paul Parquet

With a wonderful balance between sunny, herbaceous top notes and a spicy, warm and rich base, Fougère Royale smells like the cleanest, freshest facets of summertime—a waft of lavender here, some notes of hay and moss there, rounded out by vanilla, tonka, and spice from carnation and florals. Vintage Fougère Royale smells more subtle and natural than its reissued version.

Scent and Subversion

Scent and Subversion