- Home

- Barbara Herman

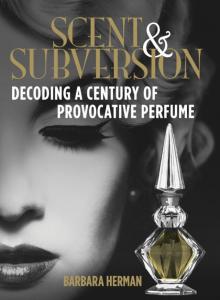

Scent and Subversion

Scent and Subversion Read online

Copyright © 2013 by Barbara Herman

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Ellen Urban

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Herman, Barbara.

Scent and subversion : decoding a century of provocative perfume / Barbara Herman.

pages cm

Summary: “An intriguing look at vintage perfume’s powerful past, including reviews of more than 300 scents, with stunning period advertisements throughout”—Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4930-0201-6 (epub)

1. Perfumes—History—20th century. 2. Perfumes—Social aspects—History—20th century. 3. Perfumes industry—History—20th century. 4. Advertising—Perfumes industry—History—20th century. 5. Perfumes—History—20th century—Pictorial works. I. Title.

GT2340.H46 2013

391.6’30904—dc23

2013027423

In loving memory of my grandmother, Nhieu Thi Tran,

a formidable woman if there ever was one.

Bourjois ad, 1926

Contents

Copyright

PART I: INTRODUCTION

My Chemical Romance: Why the Perfumed Life Is Worth Living

Why Vintage?

Take a Whiff on the Wild Side

Smell Bent: The Subculture of Perfume Lovers and the Resurgence of Scent

Scent Is Subversive

PART II:

Twentieth-Century Perfume Profiles

The Icons of Modernity:

Fougère Royale, Jicky, Chypre (1882–1919)

Fragrance Fantasias:

Shalimar, Emeraude, Chanel No. 5 (1920–1929)

The Dirty ’30s:

Tabu, Scandal, Shocking (1930–1939)

The New Look, The New Scents:

Vent Vert, Femme, Miss Dior (1940–1949)

The Bold and the Beautiful:

Intimate, Cabochard, Youth Dew (1950–1959)

Flower Power:

Norell, Fidji, Calandre (1960–1969)

A Breath of Fresh Air:

Aliage, Diorella, White Linen (1970–1979)

Think Big:

Paris, Poison, Paloma Picasso Mon Parfum (1980–1989)

Water, Water, Everywhere:

CK One, L’Eau D’Issey, Laundromat (1990–2000)

PART III:

The Future of Scent and Subversion

Scent Visionaries Antoine Lie and État Libre d’Orange’s Sécrétions Magnifiques:

Fragrance Meant to Disturb

Christopher Brosius of CB I Hate Perfume:

Mixing Memory with Desire

Sissel Tolaas:

Scent as Communication and Information

Martynka Wawrzyniak:

“Smell Me”: An Artist’s Olfactory Self-Portrait

A Brief History of Animal Notes in Perfume

Perfume 101:

How to Become an Informed Perfume Lover

Starting a Vintage Perfume Collection:

Some Tips

Acknowledgments

Glossary

Recommended Reading

Index

About the Author

PART I

INTRODUCTION

My Chemical Romance:

Why the Perfumed Life Is Worth Living

“Food, clothing, shelter, perfume.” Such was perfume’s power that for many years, this accurately depicted my hierarchy of needs. (Advertisement from 1971)

Why Vintage?

Imagine if a first edition of your favorite book slowly disintegrated each time you read it. You might be able to buy another copy at a yard sale or online, but sooner or later, there wouldn’t be a single copy left. And let’s say, because of a quirk in paper and ink, there was no way to copy its words. What imaginary worlds that reflect back and teach us about our own would be lost forever?

Sadly, this is the fate of many major and minor classic perfumes of the twentieth century, perfumes that have revealed through their liquid language how women and men lived, what they aspired to, and what was forbidden to them. Because perfumes go out of style, change formulas, or get discontinued, most of these mini novels written in liquid will simply disappear.

The threats to perfume come from multiple directions. Sometimes, brands decide to discontinue a fragrance because it doesn’t do well initially. This was the fate of two recent masterpieces: Jacques Cavallier’s Le Feu d’Issey for Issey Miyake (1998) and Isabelle Doyen’s Eau du Fier for Annick Goutal (2000). Reformulations of classic fragrances happen all the time, and because of industry secrecy, consumers simply discover on their own that the new bottle of their favorite perfume smells different. Sometimes the reformulations are by necessity. For example, birch tar was banned by IFRA (The International Fragrance Association), so Guerlain had to eliminate it from their formula for Shalimar. Perfumes are often reformulated to cut costs, using less expensive ingredients than in the original. In other cases, some perfumes are tweaked to conform to prevailing styles.

Whatever the case, Givaudan perfumer Jean Guichard recently made a confession that the perfume industry has never owned up to before: Perfumes do in fact get reformulated. He confirmed what every perfume lover who has ever picked up a new bottle of an old favorite and failed to recognize it already knows. “Consumers know their perfume better than any expert,” Guichard said. “We say nothing to consumers, but they notice when their fragrance has been changed.”

By January 2010, IFRA had instituted a ban on a long list of perfume ingredients crucial to iconic perfumes such as Chanel No. 5, Joy, and Mitsouko. This prompted Paris-based perfume historian Octavian Coifan to declare that “twentieth-century perfumery will become history.” The situation is looking even more dire now. At the time of this writing, in 2013, the EU is proposing severer restrictions on even more natural ingredients used in perfumery, to which perfumer Frédéric Malle of Éditions de Parfums de Frédéric Malle has responded, “If this law goes ahead I am finished, as my perfumes are all filled with these ingredients.” He speaks for most perfume lovers, for whom perfume is more than an accessory—it is personal memory, cultural history, and art.

Perfume is inherently fragile and evanescent, but these regulations that were affecting the very DNA of perfume made seeking out vintage perfume even more urgent for me: Time was running out to discover their disappearing styles and stories. I wanted to smell as many vintage perfumes as I could before they were gone forever. Thanks to eBay, estate sales, Ye Olde Junque Shoppes, online purveyors, and decanted samples from readers of my blog, Yesterday’s Perfume, many of these originals became mine. As I was collecting vintage, I was still seeking out contemporary perfume, but I felt there was time to learn about the new.

My obsession started off small—a decant of vintage perfume here, a bid on a full bottle of perfume on eBay there. But the flame soon grew into a conflagration, if not a full-scale, five-alarm fire, stoked by perfume books, blogs and forums, and conversations with other perfume lovers. Ironically, I would come to learn a great deal from most of my scent interlocutors through the pale light of my computer screen, my love for something so visceral facilitated through the virtual. Soon enough, my romance with what Octavian Coifan calls the “Eighth Art” was in full bloom.

Take a Whiff on the Wild Side

It was a

few years ago when I was the editor of a women’s pop-culture website that I started writing about perfume on my blog, Yesterday’s Perfume. The office manager would bring me packages of perfume I’d ordered online, and during breaks from blogging about celebrity hookups or the latest birth-control method, I’d rip them open at my desk. Trying to be discreet in the middle of an open office, I’d pop open a tiny one-milliliter vial of the decanted perfume du jour and dab it on my wrist with its plastic wand. Then, in a ritual that has become as common as having a meal or reading a book, I’d lift my wrist to my nose, close my eyes, and sniff, like a deranged junkie getting her fix.

In that work environment, it would have been appropriate for me to wear perfume in a style that has been popular since the 1990s: the office scent. Usually with citrus notes or oceanic accords that stay close to the skin—notes that project little more than “clean”—an office scent’s raison d’être is to avoid being offensive. It plays well with others. By definition, it is institutional and conformist. CK One, Calvin Klein’s 1994 unisex hit, is the perfect example of an office scent. “CK One,” writes one commenter on Basenotes.net, “prolongs that feeling of being washed and clean.” Another fan says, “This is the ONE true fragrance that could just be worn by practically anyone on earth, including newborn babies.”

As I became bored with office life, my rebellion took an invisible—but odoriferous—turn. I didn’t want to smell clean, I didn’t want to blend in, and I certainly didn’t want to smell like a newborn baby. My perfume tastes began to wander over to the wrong side of the tracks, looking for the rude, the louche, and the difficult. I wanted an anti-office scent, a perfume that would flip office culture the bird and throw a smelly Molotov cocktail through the window for good measure.

I found myself drawn to Difficult-Smelling Perfumes that subverted the clean perfume trend. Among them were vintage perfumes that took me to distant lands and told me stories about fur-clad, misbehaving women who smoked; “animalic,” erotic perfumes that smelled like unwashed bodies and deliberately overturned trite and outdated gender conventions in perfume.

In my honeymoon period with perfume, I fell in love many times. Take Bandit, Robert Piguet’s 1944 perfume for women. Its composer, Germaine Cellier—former model, reputed lesbian, and legendary iconoclast of scent—was the rare female perfumer, celebrated for her daring overdoses of extreme perfume notes. Her masterpiece, Bandit, a green leather perfume for women, was said to have been inspired by the scent of female models changing their undergarments backstage at fashion shows. Whether in fact “odor di femina” was its inspirational referent, Bandit offered a subversive olfactory ideal of femininity: It smelled like the unholy union of a bitter, snapped green flower stem, an overturned ashtray, and a leather whip freshly smacked against someone’s skin. Bandit wasn’t a demure, come-hither scent; it was a masked dominatrix lashing you with her crop. Bandit was introduced to the public during a Robert Piguet fashion show. In a fitting debut for this extreme, provocative scent, models dressed as pirates brandished weapons, and the show ended as a model smashed a bottle of Bandit on the runway, turning on her heels as this gorgeous, bitter, butch perfume filled the air.

Chanel No. 19 (1971) was gentler in its seductions. Rather than slap me with a new and shocking scent, it lulled me into an opiate-like dream state. It unfolded before me, smelling of wet earth and vegetal freshness, inducing visions of a dim, damp forest. Its magical forest intimated—now stay with me on this one—that it was populated with fairy-tale witches casting spells both good and bad. Chanel No. 19 made me realize that a well-made perfume is a Mute Invisible Cinema, with its own mise-en-scène, characters, atmosphere, and even narrative. How it conjured these poetic scenes and moods through perfume notes is a testament both to the limbic system—the part of the brain that processes memory and emotion—and to perfumer Henri Robert’s ability to manipulate it with scent molecules.

A great perfume also invites us to shore up all of our senses…

As the oldest part of the brain, the limbic system connects the brain’s higher and lower functions, and it has a privileged relationship to scent. The amygdala, one organ of that multipart limbic system, is responsible not only for helping to produce emotional responses to sensory stimuli like odors or sounds, but also for making connections between the senses. (Only two synapses separate the olfactory nerve from the amygdala.)

One drop of interesting perfume can prompt the amygdala to flood us with an emotional response. A great perfume also invites us to shore up all of our senses, to borrow their metaphors to make perfume’s story more legible, its cinema more visible. These metaphors help to translate the dizzying complexities of emotional, cognitive, and aesthetic responses that perfume can prompt.

One could argue that that the visions and moods Chanel No. 19 induced were courtesy of the limbic system’s synesthesia-simulating influence. In synesthesia, the neurological condition that produces cross-sensory perception, the synesthete may taste shapes, hear colors, or see sounds. Although only about 5 percent of the population has this intriguing “disorder,” perfume could be said to be an inherently synesthesia-prompting—or at least, simulating—object. The almost druglike, hallucinatory quality of a particularly intense perfume can inspire feelings and visions in even the most buttoned up among us. Every perfume lover has, at one point, experienced and then translated a scent synesthetically, via color (“It smells green”), sound (“It’s high-pitched”), shapes (“It seems round”), taste (“It smells sweet”), and even touch (“This scent has texture.”). Even the oft-heard critique that perfume reviewers write “purple prose” is a synesthetic metaphor!

Unlike Chanel No. 19’s Mute Invisible Cinema, Christian Dior’s 1972 perfume Diorella was an impassioned philosophical argument in perfume form. Its disquieting, overripe melon note reminded me (just momentarily) of an overheated dumpster during a New York City summer, with its sweet, sweaty smell of flowers, fruit rinds, and meat scraps mingling in their first, fetid blush of decay. Of course Diorella didn’t smell like this right away, and some people might not smell anything unusual at all. But that overripe, almost rotting smell, like a microexpression—the fleeting expression on someone’s face that reveals an unconscious, near-imperceptible, and perhaps unsavory truth—gave the perfume character. Perfumer Edmond Roudnitska, in the form of perfume rather than a philosophical treatise, teaches us that ripe smells connote death as much as they do life, and that in fact it’s the mortality of bright and alive things that makes them—and Diorella—beautiful.

Not all of the subversive scents that took me to the Wild Side were vintage. Some contemporary perfumers were pushing their creations into more daring olfactory and cultural directions than the prevailing cult of clean perfumes. Serge Lutens’s Muscs Koublaï Khän (1998), composed by Christopher Sheldrake, emerged repeatedly in online perfume forums as the bad boy of niche perfumes, gossiped about like a dude with a bad reputation. Like all bad boys, there was the good (“Perfection!” “My favorite olfactory pet”) mixed in with the bad (“The way your crotch would smell after dumping talcum powder down your shorts and running the Phoenix marathon”). In the case of Muscs Koublaï Khän, I came to discover that both of these descriptions were true, and both were compliments.

The dirty animal to CK One’s freshly washed baby, Muscs Koublaï Khän smelled like wet fur and unwashed hair and bodies, combined with the faintest, softest hint of sweet wild honey and powdery pollen. Its combination of conventional floral notes with animalic notes also evoked the smell of a man who had just taken a shower and decided to exercise without deodorant, the metallic twang of his body odor, ripe with olfactory facets of cumin, fecal civet, and hamster cage radiating through the fresh, powdery soap he’d just used.

This elegant brute of a perfume, like a pungent bohunk from a Harlequin Romance novel, had truly swept me off my feet. Its atavistic embrace of animalic base notes (albeit in synthetic form) hearkened back to vintage perfume styles, and even to the ninet

eenth-century dandy’s love of the animal-derived perfume ingredients musk, civet, castoreum, and ambergris. Muscs Koublaï Khän was released by the exclusive brand Les Salons du Palais Royal Shiseido in 1998, a few years after the crystalline transparency of Bulgari’s Au Thé Vert Au Parfumée (1992) and the unisex clarity of Calvin Klein’s CK One (1994). A true dissident in the House of Clean, Muscs Koublaï Khän signaled a return of impolite bodily smells in perfume, smells that had flourished up until the late 1970s, when their popularity began to wane.

In this 1955 ad for Ambush, a well-dressed woman wearing Ambush—and a tiny smirk—awaits her prey like a spider on a web.

Once I was done sniffing Muscs Koublaï Khän, I did what any perfumista worth her salt would do next. I went deeper, and got hazed at the queer, punk Parisian frat house État Libre d’Orange (“Free State of Orange”) via its truly outrageous perfume, Sécrétions Magnifiques, a perfume whose original bottle announced its contents with a charming cartoon rendition of an ejaculating penis.

Sécrétions Magnifiques starts off innocuously enough with a soft, floral note. But things get weird very quickly, as the scent of blood, sweat, and semen—shocking biological accords never before used in perfume—arrive like an assault to the senses. This “olfactory coitus,” according to Sécrétions Magnifiques’s original website copy, smells like “like blood, sweat, sperm, and saliva … when masculine tenseness frees a rush of adrenaline in a cascade of high-pitched aldehydic notes.” If animal notes are the erotica of vintage perfumes, Sécrétions Magnifiques’s biological accords are the new millennium’s first olfactory pornography, exposing body parts where they were earlier merely suggested and using olfaction to turn the body inside out.

SM (note the abbreviation, referencing sadomasochism) smells like fresh spunk, and, as many traumatized sniffers have remarked, also like a car accident or a hospital emergency room. Lest you still aren’t quite getting the gist of how impolite this scent is, even Perfumes: The Guide writer Luca Turin, who found the scent inoffensive and even pretty, remarked on its “bilge” note, a word that describes stagnant water that gathers at the base of a ship.

Scent and Subversion

Scent and Subversion